A Revenue Operator's Guide to Change Management

Because you can't achieve impact without adoption

Almost any work in operations affects other people and requires their adoption or support to be successful.

You may not be trained for this—but if you’re an operator, you’re also a change manager. It’s as simple as that.

It’s core to the job

The most common change management strategy might be described as “hope for the best.”

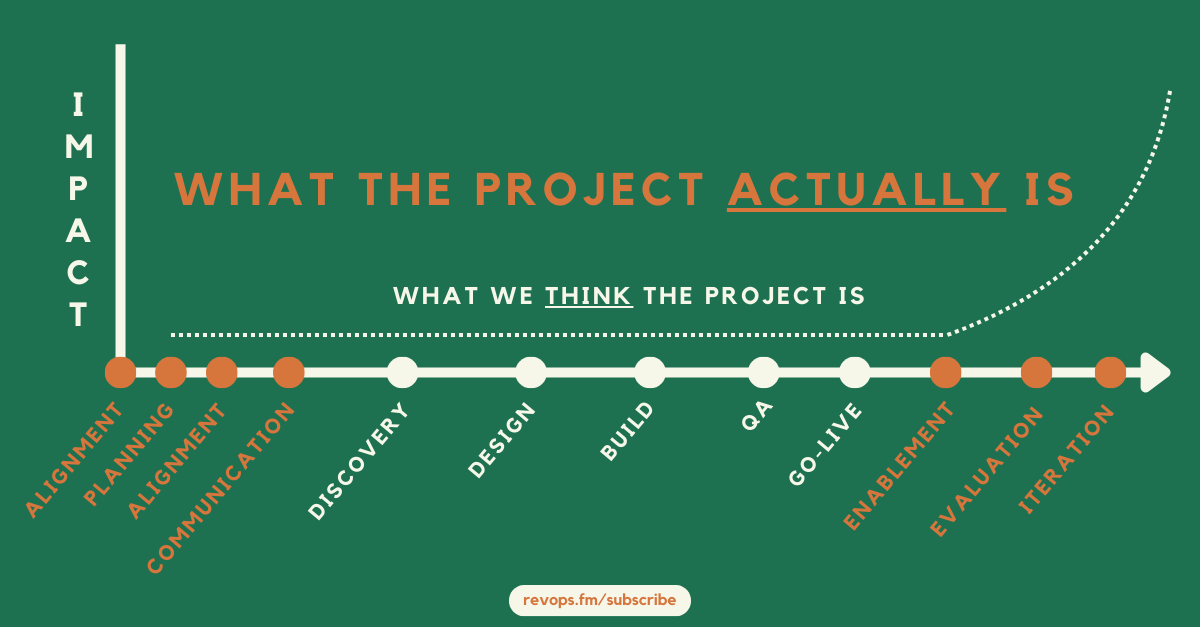

Even when it’s included in the plan, change management is often treated as an extra—an afterthought to be tacked on to the end of a project and perhaps addressed with a bit of training or documentation.

This usually won’t be sufficient. Change management has to be incorporated into the foundation of how you operate, starting with initial planning of a project and extending well beyond the go-live date.

The impact when change isn’t managed well

What happens if you don’t manage change properly?

Best case: it will make your job and life harder, forcing you to spend time on re-work or re-enablement.

Worst case: it will cause your initiative to fail, damaging your credibility and job security.

Practical examples:

- You design a new dashboard without consulting all stakeholders. Executive leadership doesn't adopt it and continues to use other ad-hoc reports, leading to fragmented sources of truth.

- You want your sales team to start asking prospects "how did you hear about us?" so you roll out a process and some new fields. Sales doesn't see the benefit and generally ignores you. The field has a 1% completion rate.

- You roll out a new CPQ system. Despite the training and extensive documentation you prepared, reps feel blindsided, leading to general confusion, anger, and frustration when the system goes live. You find yourself under intense executive scrutiny for the impact on pipeline and forecast accuracy.

- You create a self-serve model for marketers to launch their own campaigns in your marketing automation platform. You have templated assets and clear documentation, but marketers struggle with the new process and continue to barrage you with questions. It's harder to get campaigns out the door, and word trickles up to your CMO.

- You rearchitect your lead flow to make it more streamlined, robust, and scalable. The new design is objectively superior, but some operators on your team don't understand it and now struggle to make changes that interface with it. The last example is interesting, as it shows how even largely “technical” or internal operations projects aren’t exempt from needing change management.

Operators need to manage their own change cycles too.

Why we struggle

Few of us have formal change management training.

Also the type of people who enter operations tend to be left brain thinkers—analytical and process and data-oriented.

A poorly functioning system is frustrating, but at least it can be de-bugged, re-architected, and optimized. It’s a logical machine.

Human beings are far more complex to “debug” and often aren’t entirely logical. Sometimes they can be irrational, unreasonable, and even hostile.

The solution

I have no silver bullets for you, only insights and tactics learned over the years, usually through repeated mistakes.

Make change management a priority

It’s critical to recognize the necessity of managing change and to integrate it into our workflows.

It should be part of the discussion whenever a new project / idea / initiative is brought to the table and fully baked into the plan,

Develop situational awareness

Your change management requirements are going to be driven by your context and your project.

Regardless of the project, driving change in a young startup of five people is far easier than in a massive 10,000 person company.

And regardless of your context, implementing a small change that requires no behavior modification is different than a huge project that requires people to completely change their routines.

So as you consider any new initiative, take stock of your context and how people will be affected.

Some questions to ask yourself:

What teams and people will be impacted by this change?

Does it require an active change in behavior?

Does it affect information or systems people use regularly?

Does it impact sensitive topics like incentives, performance reporting, financial data, etc?

Is there a company “history” that might come into play? Personal sensitivities? Baggage or tension?

Practical example:

Your company's suite of products is growing in complexity, and you see a clear need to roll out a CPQ system in your CRM.

However, there was a similar initiative that failed miserably a few years ago. Many reps remember this failure and the pain it caused.

This company history will dramatically increase the change management requirements for any new attempt in this area. Understanding and addressing concerns

There are always reasons why people don’t embrace (or even actively resist) change.

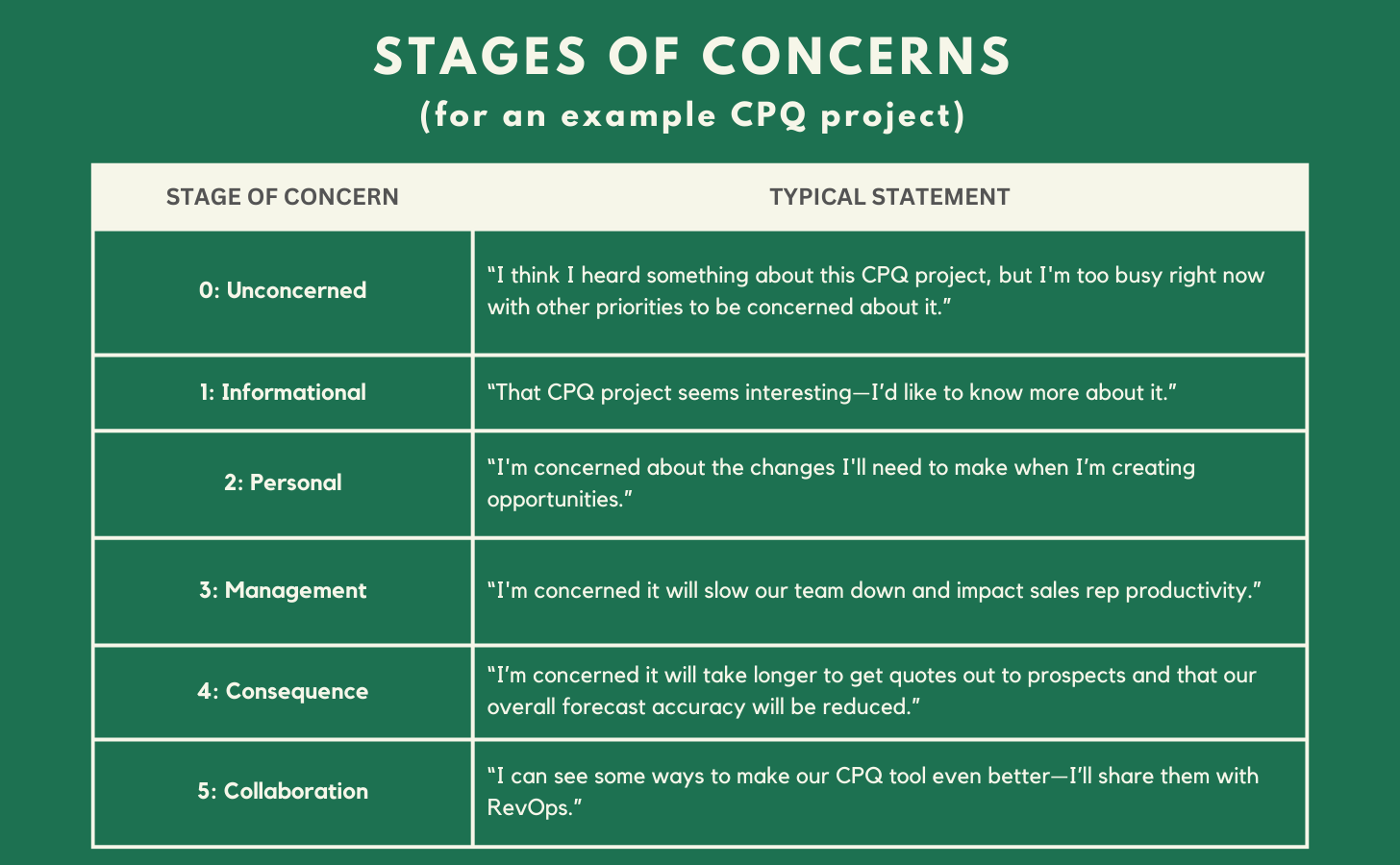

“Stages of Concern” is a useful tool to help identify and address those reasons.

It’s part of a broader framework called the Concerns-Based Adoption Model, originally designed for use in an educational context.

The Stages of Concern model how an individual moves through different attitudes towards a particular change, progressing from indifference / apathy to a focus on broader impacts and eventually to collaboration.

Here’s a table of the different stages and a typical statement associated with each (I’ve adapted them to a RevOps context, continuing with the example of our hypothetical CPQ project).

You can use this framework in a few ways.

Creating empathy

Before one major change at a previous role, we applied the Stages of Concern to proactively identify and anticipate the potential concerns that stakeholders might have.

There are many possibilities:

Seems disruptive / too busy / can’t be bothered

Lack of understanding

Fear of increased work / reduced productivity

Fear of reduced visibility / access to information

Fear of impact on ability to perform / loss of credibility

Fear of the unknown

Politics / turf wars

Working through the stages helps you get inside the head of your stakeholders and make sure you address their concerns in your messaging.

Gauging impact

The Stages of Concern was originally designed as an assessment model with a questionnaire to identify the stage people were at.

While I haven’t applied this formally, you could take a similar approach with a survey or 1-1 interviews with your stakeholders. This helps you understand your progress and how to communicate better.

Practical example:

You distribute a brief survey to your sales team, and the majority of them agree most with the statement, “I think I heard something about this CPQ project, but I'm too busy right now with other priorities to be concerned about it.”

This means the team is largely unaware of or indifferent to your initiative—they're at Stage 0 (Unconcerned).

So your primary goal is to help them become aware of and interested in your project.

A few weeks later, you give the same survey and the team now aligns most with the statement, “I'm concerned about the changes I'll need to make when I’m creating opportunities.”

You're now at Stage 3 (Personal).

Your goal now becomes to show them how the opportunity creation process will be simple, fluid, and make their lives easier. Creating your communication plan

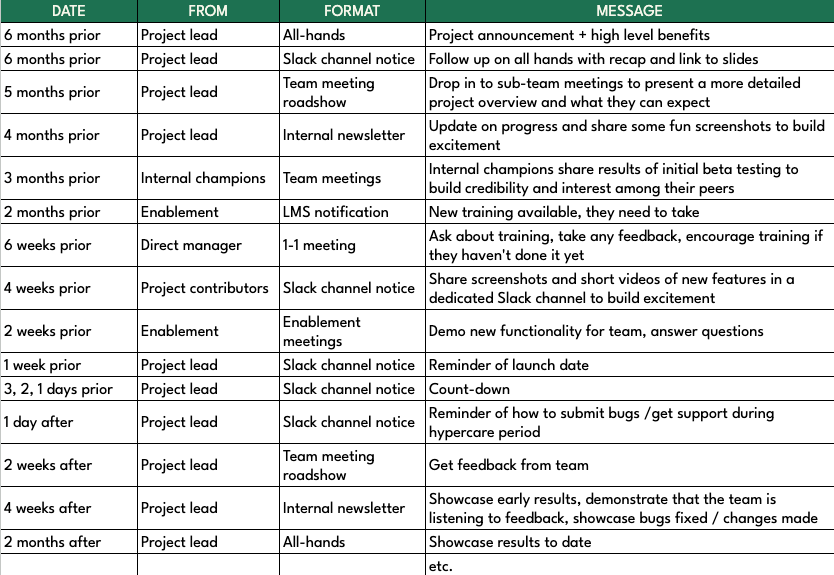

A Slack message is not a communication strategy.

You need to think of this like a multi-channel nurture, where you reach people with a variety of messages in a variety of formats from a variety of personas over time.

Of course, you need to right-size it for both the size of your company and the complexity / impact of your initiative.

Here’s an example communication plan for our CPQ project:

The goal is to keep up a steady drip of information that informs, educates, and engages.

If done well, it should both address concerns and build excitement. Yes, it’s a lot like marketing. 😊

You’ll also notice it doesn’t stop at the delivery date. It should continue until the new initiative becomes the status quo.

Don’t change alone

If you look closely at the communication plan, you’ll notice it’s not just the project owner being a lone voice in the wilderness, hoping that the team will pay attention.

Change management is most effective as a team sport, and so you should be cultivating allies, sponsors, and supporters to help drive the process.

Top down

The most natural support is from your own executive leadership as well as the leadership of impacted teams.

This kind of alignment is a critical part of project planning, so ideally you have these people bought in by the time your project has the green light.

Now you need to keep them engaged throughout the process—both as part of managing their own change cycle and so they can reinforce your messages with their team.

People may ignore Slack messages from ops, but they’ll be unlikely to totally disregard a message from their manager in a 1-1 saying “this is important.”

Bottom up

People are also highly influenced by their peers, especially those perceived as influential top performers.

You should identify these people at the start of a big project and enlist them in the process. If the impacted team is large enough, you can form a smaller “advisory committee” that gets early access to new ideas / features, gives feedback, and helps communicate back to the broader team.

This is a great way to course-correct early if something is wrong and to turn the most influential team members into evangelists.

If an influential team member has concerns, including them in the process can also be an effective way of diffusing those concerns and making them feel a sense of ownership in what you’re delivering.

Conclusion

This whole thing can be uncomfortable, and it can feel like a lot of extra work.

It’s easy to cut corners or take shortcuts.

But keep this in mind: if our goal is to drive impact, then we only achieve that when our work is fully adopted and operational.

Change management is how we do it.